We’ve all heard meteorologists use the term lake-effect snow. But what does it mean? How does it form, and how far does it travel? Does it only form around the Great Lakes? These questions answered and more.

Lake-effect snow explained

During winter, snow falls from moisture above in the clouds, but snow also forms through another phenomenon known as lake-effect snow.

During regular snowfall formation, tiny ice crystals in the clouds stick together forming snowflakes. According to the UK Met Office, when enough crystals stick together, they become heavy enough to fall to the ground. This typically occurs at around 32 degrees F (0°C). Precipitation falls as snow when the air temperature is below 35.6 F.

Differing from the usual formation of snow is lake-effect snow, according to the National Weather Service (NWS), where moisture from a large body of water moves upward into the clouds and returns downward as snow.

The majority of lake-effect snow forms between late autumn and the first part of winter. The Great Lakes remain unfrozen and relatively warm compared to the colder air flowing down across the region from Canada.

Lake effect snow can vary in intensity, even piling up at such a rapid pace it appears to be a widespread blizzard. A lake-effect snow event can last only a few hours or can go on for days. One of the largest Lake-effect snowfall events occurred in November 2014, which resulted in 5 feet of snow falling over two days near Buffalo, New York.

Like-effect snow can sometimes travel as far as 100 miles away, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA).

How lake-effect snow is created

As its name suggests, lake-effect snow requires a large body of water in order to form.

Lake-effect snow begins as cold Arctic air moves over warm lake waters. The lake surface adds heat and water vapor to the cold air mass. Next, the water vapor condenses in rising air to form clouds. Then, snow falls over the lake and onto the downwind shore.

It’s worth noting that one might assume cold land and water temperatures increase the snow, but that’s not the case. Lake-effect snow is more effective if both the land and water temperatures are higher.

“Meteorologists look for a temperature difference of 23 degrees Fahrenheit or greater between the lake water and the air approximately 5,000 feet above the surface of the lakes,” says Brian Wimer, Senior Snow Warning Meteorologist for AccuWeather. “The greater the temperature difference between the lake and the air above, the heavier the lake-effect snow will be.”

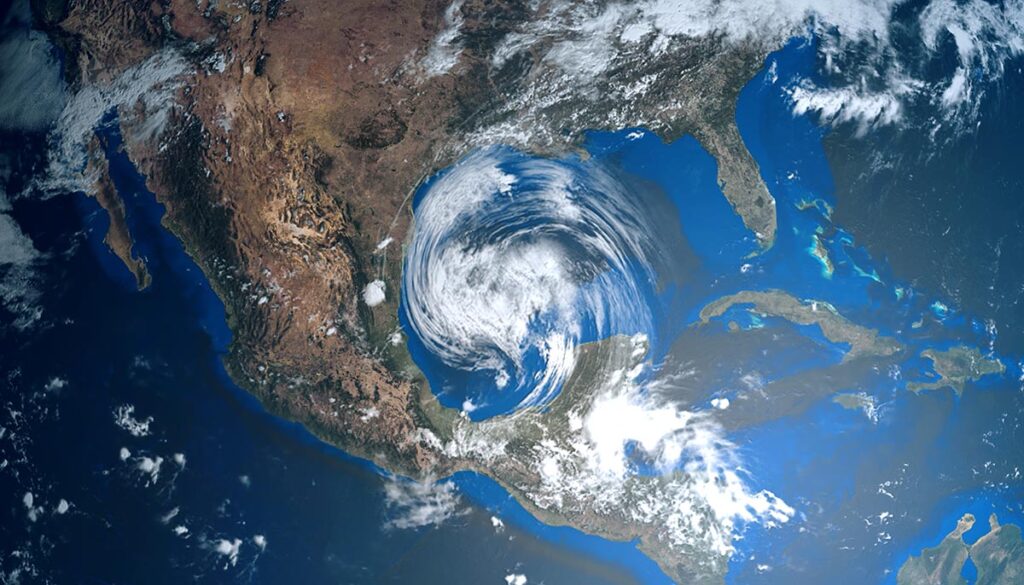

Lake-effect snow typically forms in bands, and they can be seen visually from above, moving in lines. Areas affected by Lake-effect snow are called snowbelts.

Does lake-effect snow occur anywhere besides the Great Lakes?

The answer is yes. However, nowhere else does the amount of Lake-effect snow occur in such a pronounced way that it affects ground and air transportation than it does over the southern and eastern shores of the Great Lakes of North America, according to todas-uwyo.edu.

So where else does Lake-effect snow occur? One place is near Lake Baikal in Russia. It also occurs on the west coasts of northern Japan, the Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia.

Ocean-effect or bay-effect snow

When snow formation occurs over bodies of saline water, meteorologists use the term Ocean-effect or bay-effect snow instead.

This type of snow occurs in areas near the Great Salt Lake, Black Sea, Caspian Sea, Baltic Sea, Adriatic Sea, and the North Sea.

Areas in the US most affected by lake-effect snow

The most-affected US areas include the Upper Peninsula of Michigan (most in the US, can average over 200 in of snow per year); Central New York; Western New York (Tug Hill in New York’s North Country region has the second-most snow amounts of any non-mountainous location within the continental US); Northwestern Pennsylvania; Northeastern Ohio; Northeastern Illinois (along the shoreline of Lake Michigan); northwestern and north-central Indiana (mostly between Gary and Elkhart); northern Wisconsin (near Lake Superior); and West Michigan.