Summer storms are a common sight, especially in warmer climates. While it’s not impossible to see thunder and lightning rumbling within a snowstorm, it’s much less likely than a thunderstorm in June. Why are lightning storms so much more frequent in the summer than in other seasons, though?

It’s all related to humidity and moisture in the atmosphere.

How Storms Form

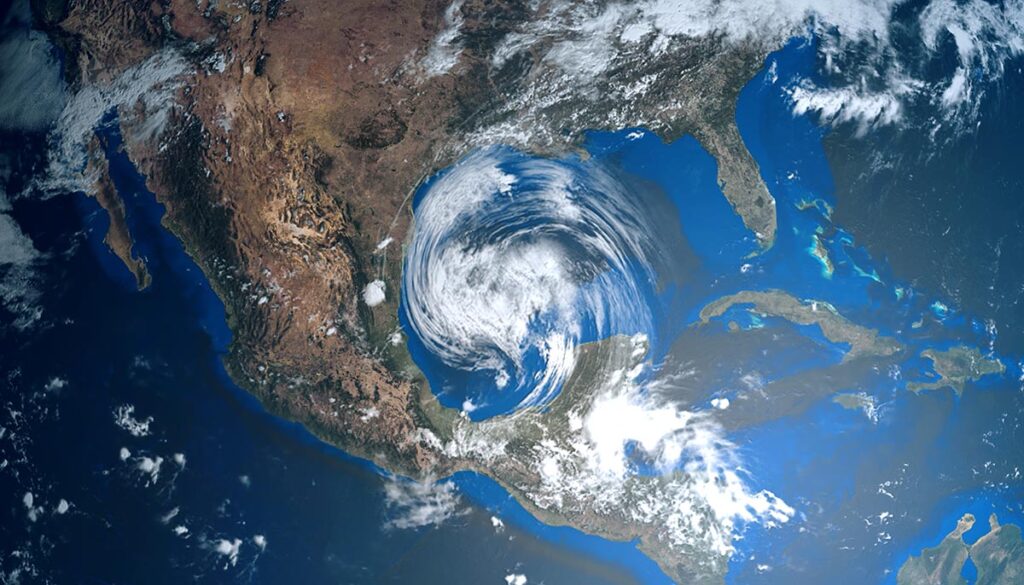

The clouds that eventually give rise to thunder and lightning form when water from the planet’s surface evaporates and rises in the atmosphere. Water vapor collects high above the ground, where it cools and coalesces into clouds. Both moisture and rising warm air are required for those clouds to grow enough to become thunderheads. The amount of humidity and heat required for this formation is much more abundant in the summer months, especially in regions like the Southeast United States.

Once a cloud has grown large enough to darken the skies and threaten rain, it has all the elements needed to generate lightning. Rising water vapor bumps into the ice particles and droplets inside thunderheads, causing electrons to be knocked free of the H2O molecules. This electron movement results in a process called “charge separation” and the formation of an electrical field.

Charge separation results in the colder regions of the cloud higher in the atmosphere becoming negatively charged. The bottom of the thunderhead becomes positively charged due to the electron concentration moving to the warmer water vapor. This process continues with rising water vapor carrying the positive charge to the upper part of the system and rotating the electric field. Most thunderheads become proper storms when this process is self-sustaining, forcing a negative current to the bottom of the cloud.

Electrical Field Generates Lightning

At this point, a thunderstorm is essentially a natural Van de Graaff generator. The electrical field in the atmosphere causes electron repulsion in the Earth’s surface, creating a huge positive charge on the ground. When the difference between the ground’s positive charge and the cloud’s negative charge becomes too great, electrons achieve equilibrium by opening an electric current between the two positions.

That conductive path is what we call lightning. The sudden discharge of high-voltage electricity is a surge of electrons traveling to the ground, superheating the air and generating plasma for a fraction of a second. So much energy is released during this event that the center of a lightning bolt is five times hotter than the Sun’s surface.

Thunder Follows Lightning

This discharge results in a very sudden displacement in the atmosphere. The thunder that follows lightning is a sonic boom caused by the electrical current splitting the atmosphere. Thunder always takes longer to reach an observer on the ground than lightning because sound waves travel more slowly than light radiation.

As a result, even casual observers can determine how far away a lightning strike is by counting the seconds between the flash and the arrival of thunder. For every five seconds that pass, the sound has traveled about one mile.

There you have it! For thunder clouds to form, hot air and fast-rising moisture need to generate a strong electrical current in the upper atmosphere. Such a situation is much likelier in warmer months, leading to a high number of summer storms.